Cholera

Cholera: origin and transmission

Cholera is a toxic contagious enteric epidemic infection caused by Vibrio cholerae, serotype O1 or O139. It leads to acute watery diarrhea which can rapidly evolve to dehydration and death if left untreated. Most patients will recover with oral rehydration therapy; however, some patients will require rapid intravenous rehydration. The death rate can be less than 1% of cases with adequate treatment; however, this can be as high as 50% if cases are left untreated.

Cholera is transmitted via food or contaminated water and can be prevented by ensuring clean water, good sanitation, and effective hygiene. Cholera can also be controlled through vaccination. The cholera vaccine is an oral vaccine consisting of 2 doses that are administered two weeks apart.

Cholera in endemic in south-east Asia and causes outbreaks in Africa and the Americas. An increased risk of cholera has been noted in parallel with the ever-increasing size of vulnerable populations living in unsanitary conditions, in slums were basic sanitation infrastructure is lacking, or due to a breakdown of the infrastructure as a result of war or a natural disaster. Cholera affects n estimated 1.3 to 5 million people worldwide each year and causes 21,000–143,000 deaths a year.

Mapping the burden of cholera

Concentration the effort in the most affected places

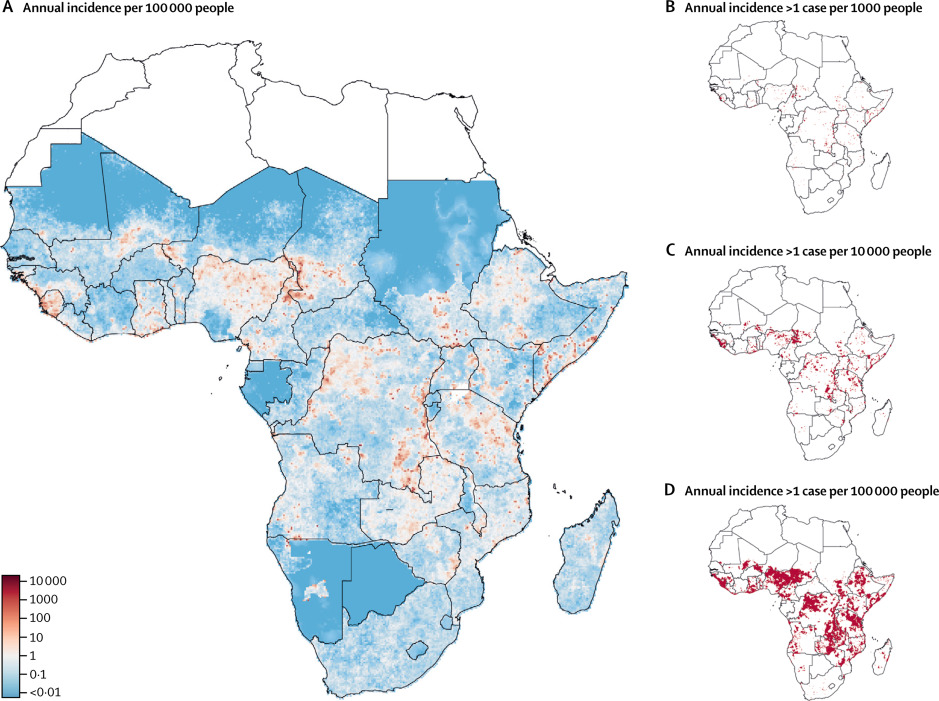

Epicentre and the Johns Hopkins University have mapped the areas where cholera is most prevalent in Africa using modeling techniques. Results indicate that a concentrated effort in just 5% of all districts in Africa could reduce by half the disease burden in the continent. These findings are the linchpin of the Cholera Global Roadmap to 2030, which outlines the strategy to eliminate cholera transmission as well as providing the key rational for cholera control investment case.

Understanding cholera outbreaks

Better estimates despite underreporting of cases

Epicentre provides field epidemiology support to Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to describe cholera outbreaks in terms of time, place and person. Epicentre has developed as well models to better understand the cholera epidemics spread, as it has been recently the case in Yemen4. In addition, Epicentre has shown using spatial epidemiological methods that cholera spreads in clusters.

Exploring suitable intervention strategies

Epicentre is exploring a better intervention strategy referred to as case-area target interventions, which can include WASH interventions, ring vaccination as well as distribution of antibiotics to household members. This strategy consists of containing the first foci of infection. The first results observed in Juba (South Sudan) were encouraging.

This strategy called CATI (for Case-Area Targeted Intervention) is now being evaluated in DRC, Cameroon and Zimbabwe to confirm its effectiveness.

Current evidence supports a high-risk spatiotemporal zone of 100 to 250 meters around case-households in which a case has been detected for 7 days. Based on national policies, local context, and operational considerations, MSF decides on the content of the CATI kit to be deployed (water sanitation and hygiene measures at the household level, active case finding, antibiotic chemoprophylaxis and/or single-dose oral cholera vaccination, radius of intervention) and the prioritization strategy to be implemented. The Epicentre study evaluates the effectiveness of the CATI strategy during an acute cholera outbreak, with clearly defined measures of the effectiveness of the CATI package. It will compare rapid response and the implementation of a "CATI kit" versus actions delayed by operational constraints. It will also estimate the feasibility, costs, and implementation process of this approach.

Optimizing detection for faster intervention

The reference method for diagnosis is laboratory confirmation by culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from stool samples. However, the crucial lack of laboratory facilities in countries where cholera is endemic means that confirmation takes an extremely long time, and most cases go untested.

In recent years, rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) have been developed to facilitate diagnosis directly at the point of care, without the need for a laboratory. More straightforward than PCR or culture, which require equipment and qualified personnel, RDTs require no special skills and can be carried out quickly and easily. However, they do have limitations in terms of accuracy of results, and still raise several questions: can they replace the reference test for identifying a cholera epidemic? Are their results sufficient to estimate the true incidence of cholera in areas with very different incidences? To answer these questions, Epicentre is conducting a GAVI-funded study in DRC. The main objective is to analyse the current surveillance system in the field and find innovative solutions so that the Ministry of Health can integrate RDTs into existing cholera surveillance without too much effort.

A qualitative study is also planned in all the sites to gather the testimonies of health workers at all levels on the feasibility and implementation of the use of RDTs.

At the end of the study, it should be possible to issue recommendations on the use of RDTs and the choice of sampling strategies depending on the context, which will help to improve surveillance of this disease in all the countries affected, and ensure that preventive measures such as vaccination are implemented more rapidly and on the basis of concrete evidence.

Cholera vaccination

Vaccination as a public health tool

Before 2012, cholera vaccine was almost exclusively a traveler’s vaccine and not a public health tool. In 2012, MSF conducted the first vaccination campaign in Guinea with Shanchol, a newly WHO prequalified vaccine, and analytical and descriptive epidemiological studies conducted by Epicentre shown the feasibility of conducting such a campaign as well as the safety, efficacy, and acceptability of the vaccine5. This was an important step that contributed to the creation of the global cholera vaccine stockpile in 2013. Since then vaccination has become a standard tool in the fight against cholera.

In 2013, a global stockpile of cholera vaccine was set up by the WHO with the support of GAVI. Since 2021, cholera has been on the rise again worldwide. These epidemic waves have led to a very high demand for vaccines, putting a strain on the global stockpile of these vaccines. In October 2022, the shortage of vaccines led the International Coordinating Group (ICG), which manages the vaccine stockpile, to recommend a single dose of vaccine, whereas it had long recommended a two-dose vaccination schedule.

Since it is essential to intervene quickly in the event of an outbreak, and the two-dose schedule slows down the speed of the vaccine response, Epicentre the feasibility of controlling the outbreak spread by administering a single-dose. Results from our case-control studies conducted in Zambia and South Sudan indicated that the short term protection of single-dose is similar than two-dose protection in the short term.

In April 2024, the WHO prequalified a new oral cholera vaccine (OCV), Euvichol-S, which should enable the only cholera vaccine manufacturer at present, EuBiologics, to produce more vaccine.

Defining the optimal interval between two doses of vaccine

The manufacturers of the oral cholera vaccine (OCV) recommend an interval of 7 or 14 days between two doses. It is not always possible to carry out two mass vaccination rounds within this timeframe, and many campaigns to date have used a longer interval. Recent evidence suggests that a longer interval between doses of OCV may result in equivalent seroconversion rates and better stimulation of mucosal immune responses after the second dose. Epicentre is currently conducting an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority immunogenicity trial in Guinea comparing humoral immune responses to OCV in two intervention arms (6 and 12 months between OCV doses) versus a control arm (standard 14-day interval). The aim is to determine whether the humoral immune response is non-inferior between these different oral cholera vaccine administration schedules. If so, a longer interval between doses could then be considered as an alternative to the currently recommended 14-day interval.

Epicentre is part of the oral cholera vaccine working group at the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE). Epicentre is also member of the Global Task Force for Cholera Control and actively participates in several working groups and chairs the cholera surveillance working group

Evaluating Vaccination Campaigns in DRC

Epicentre launched an operational study in spring 2021 to evaluate the impact of a preventive oral vaccination campaign in cholera hotspots in the DRC, with funding from the Wellcome, UK AID and Foreign and Commonwealth and Development Office, in conjunction with MSF activities and with the support of the DRC Ministry of Health and the National Program for the Elimination of Cholera and the Control of Other Diarrheal Diseases (PNECHOL-MD). The objective is to monitor the incidence of cholera after preventive vaccination campaigns for at least two years in one rural and one urban area, and to gain a better understand the impact of the vaccine on the level and characteristics of disease transmission.

Preliminary results show that coverage in the urban area of Goma is lower than expected based on administrative coverage. In the health areas vaccinated in 2019 and 2020, coverage for one dose is around 50%, and coverage for two doses is down to 13%. The piecemeal vaccination strategy, targeting only certain parts of the city and not others, vaccination in several stages and population movements in Goma have tended to dilute vaccination coverage. On the other hand, post-campaign coverage in Bukama is high, with around 85% of people aged over 15 and almost 90% of under-15s having received at least one dose, thanks to a vaccination strategy well adapted to the population's lifestyle.

The combination of clinical surveillance, serological surveys, and monitoring of infected households will also contribute to a better understanding of the dynamics of cholera transmission in endemic settings and inform strategies to be put in place.

A 2nd phase of this study, funded by Wellcome, has just begun. It includes an evaluation of the efficacy of the oral cholera vaccine using a case-cohort study, a series of multi-indicator surveys in Goma and Bukama (vaccination coverage, incidence of suspected cholera cases, mortality and population movements) and qualitative surveys to understand the factors influencing vaccination coverage, such as the reasons for non-vaccination and population movements.