Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance refers to the mechanism whereby bacteria mutate thereby making antibiotics ineffective. Irrational use of antibiotics has created selection pressure on resistant bacteria that may be responsible for some serious invasive bacterial infections. These infections then require last-line antibiotics that are both costly and increase the risk of complications and even death.

A growing problem and threat

Antibiotic resistance has become one of the greatest threats to global health. Resistant bacteria already cause more than 700,000 deaths globally every year and the annual toll would climb to 10 million deaths in the next 35 years.

Lack of data is problematic

There is scant information on antibiotic resistance in low-income countries and even more so in the regions and among the populations where Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) works. This is principally due to the lack of laboratories. This means that antibiotic treatments are often prescribed on an empirical basis and this may not be effective if the infection is due to resistant bacteria.

Epicentre is working to provide better descriptions of severe bacterial infections and their antibiotic resistant to strengthen the rational use of antibiotics. This is a primary issue if we want to limit the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Understanding antibiotic resistance in difficult settings

In order to better understand the scale and nature of the problem, Epicentre concentrates its efforts in describing the epidemiology of antibiotic resistance in the community and hospitals in low-income settings where MSF works.

For example, in sub-Saharan Africa invasive bacterial infections in children under the age of 5 that are acquired in the community or in hospitals (bacteremia and meningitis); and osteomyelitis in the war-wounded in the Middle East. We also investigated infection in patients suffering from serious burns in Haiti.

Regional variation and antibiotic resistance

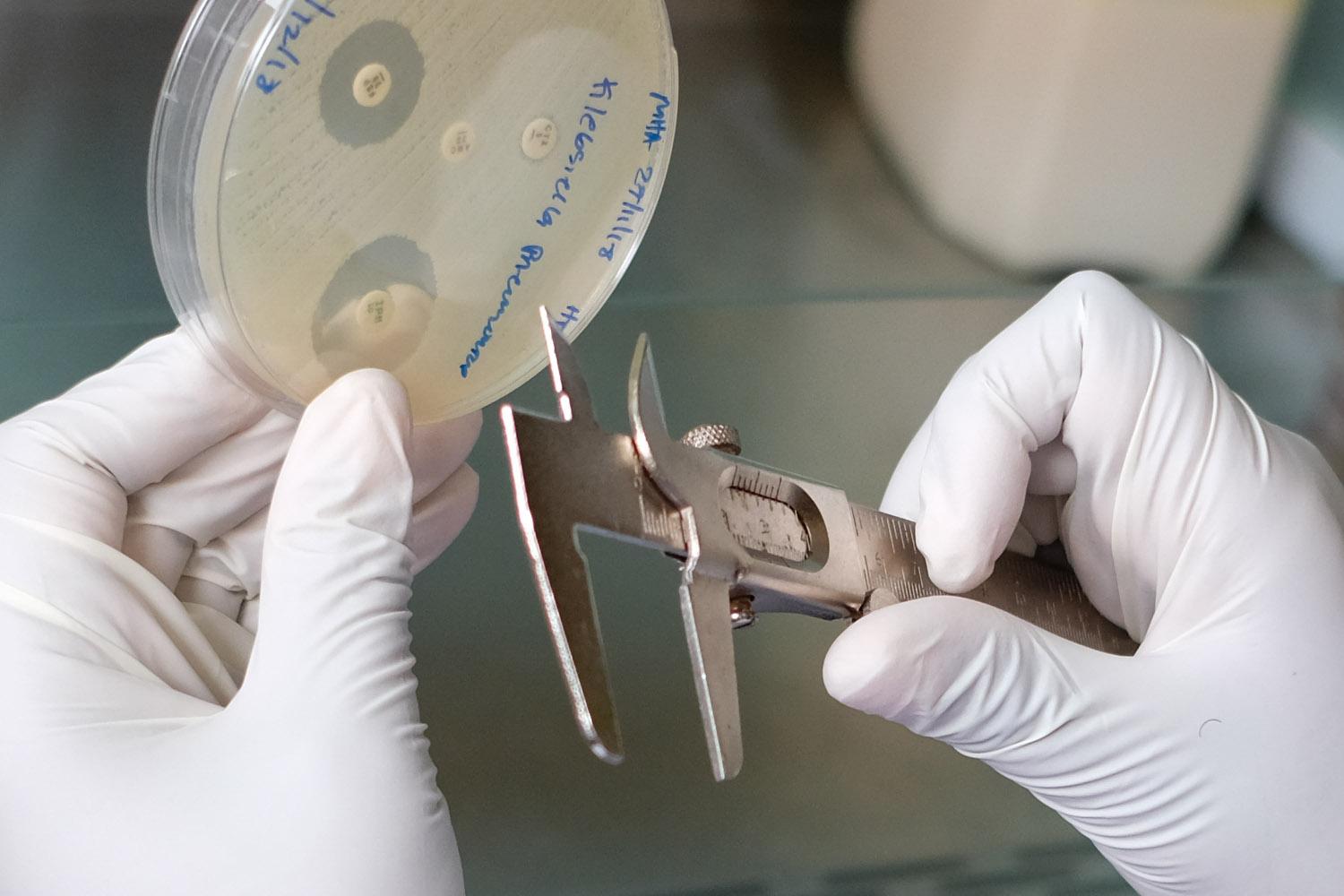

Comparisons between West Africa, East Africa and the Middle East indicate there is considerable variation in the types and proportions of antibiotic resistance. These complexities and local differences need to be understood and taken into account when adapting therapeutic protocols.

Epicentre has monitored the evolution of antibiotic resistance at its research centers in Niger and Uganda for many years, and this shows a worrying trend in multiresistance.

Our 2008 study into septicemia in children in Niger, showed no enterobacterial resistance to ceftriaxone, but results from our 2018 investigation show that 15% are resistant to this antibiotic now. Similarly, in Uganda, between 2009 and 2012, 2% of meningitis cases were resistant to ceftriaxone between 2009 and 2012, compared with 9% for bacteremia in 2015-16.

Epicentre’s carriage study in Niger in 2017 of intestinal multiresistant bacteria indicate high levels of antibiotic consumption in the general population. A total of 90% of the population (of all ages) carry multiresistant bacteria.

Antibiotic prescribing practices in Niger and Uganda

With funding from the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), Epicentre conducted a retrospective quantitative and qualitative study to learn more about paediatric antibiotic use in Uganda and Niger using 2019 data, including understanding how healthcare workers choose their antibiotic prescriptions for children.

The first finding is fairly positive, since 78.2% of the antibiotics prescribed in Niger and 68% in Uganda belong to the "Access" category of the WHO "AWaRe" classification, i.e. the group of antibiotics least exposed to the risk of resistance. The remainder of the antibiotics prescribed belonged to the "Watch" category, i.e. antibiotics recommended for specific and limited indications, and none belonged to the 3rd category known as "Reserve", which corresponds to antibiotics that should only be used as a last resort, when all other antibiotics have failed.

However problems with the availability of antibiotics in hospital stocks can lead prescribers to change antibiotics during the course of treatment or require parents to buy them at their own expense outside hospital, which can lead them to resort to another, less expensive antibiotic, or even to shorten the course of treatment. The qualitative study also shows that antibiotic prescriptions are determined more by the availability of antibiotics and their ease of administration than by therapeutic rationale.

Most prescriptions are made empirically, without using microbiological assays, which are rarely accessible or too expensive. Health workers in both countries recognize their lack of knowledge about antibiotic stewardship. This contributes to the rise in broad-spectrum antibiotic prescriptions, with the addition of a new antibiotic in the event of failure, without considering the risks in terms of resistance. An additional phenomenon is emerging in Uganda: the pressure exerted by medical representatives.

Testing in our own laboratories

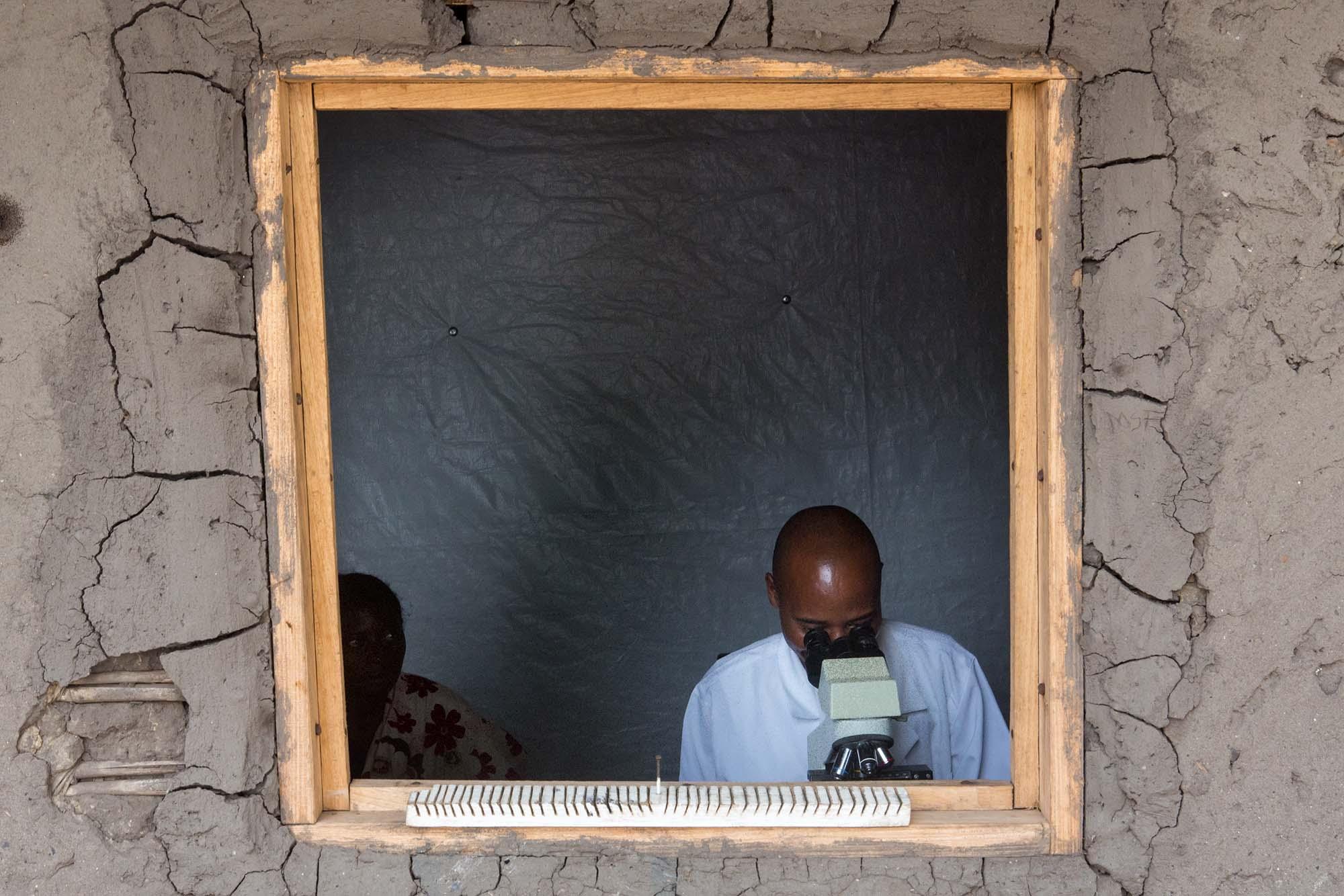

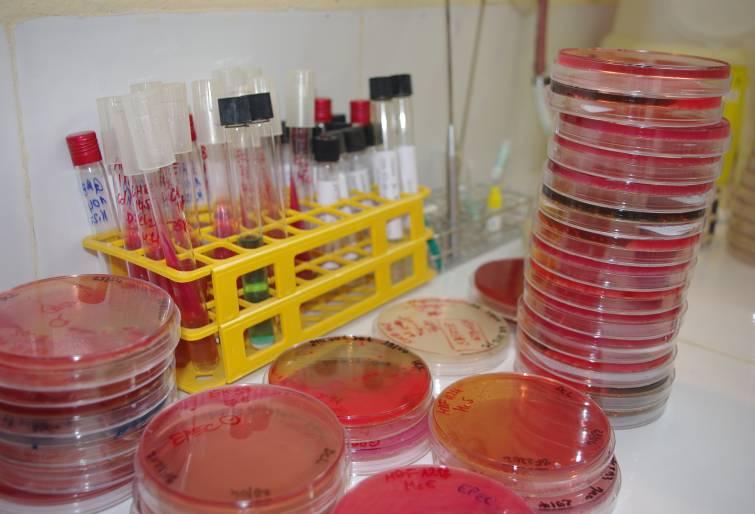

The bacteriological investigations of all these studies in Niger and Uganda are done through the bacteriology laboratories in our research centers in Niger and Uganda that provide important data in countries and regions with limited access to quality bacteriology laboratory.

Important collaborations with reference laboratories allow us to refine our research and to investigate in more detail the mechanisms of resistance, for example by molecular biology.

Mini-Lab: A transportable laboratory for MSF's field operations

The Mini-Lab project aims to design and build an all-in-one clinical bacteriology laboratory that is autonomous, transportable, affordable and, above all, adapted to MSF's field operations. This concept, developed by MSF with its partners, is also intended to be made available to healthcare workers in countries with limited resources. Epicentre evaluated the performance and ease of use of the Mini-Lab integrated into the clinical routine of an MSF-supported hospital in Carnot, Central African Republic, which had no prior access to microbiology.

Between September 2021 and February 2022, 835 patients were included in the study, with a total of 960 blood cultures.Positivity rate with pathogens was 12.5%. Over 121 pathogens identified in the Mini-Lab, 74 have been tested with reference methods so far and 68 (92.0%) gave identification results concordant with the Mini-Lab with 97.4% agreement to genus.

After the initial training, the laboratory technicians reported that most aspects of the Mini-Lab were easy to use; after three months' experience, they reported that the preparation, identification and reading of the antibiogram were straightforward. The evaluation of the laboratory technicians' skills after the initial training gave very high results (>90%) and 100% after 3 months. The Mini-Lab's performance was very good overall, and no major malfunctions preventing its deployment were identified.

The Mini-Lab has since been deployed in Aweil, South Sudan, in April 2022.

Antibiotics and the treatment of severe acute malnutrition

Epicentre also evaluated the effect of using antibiotics to treat severe malnutrition without complications. The results of the treatment of 1,776 severely malnourished children who received antibiotics only on clinical indication were compared with those of 6,185 malnourished children who received amoxicillin systematically on admission to the nutritional programme. No difference in the rate of nutritional recovery was observed between the groups. There is every reason to believe that the systematic use of antibiotic therapy in the treatment of malnutrition is unnecessary and may, on the contrary, encourage the emergence of resistance.

A double-blind trial - with a control group using routine amoxicillin for uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition in children versus placebo - conducted in 2,412 children in Niger, confirmed this conclusion. It showed no significant difference between the groups in terms of nutritional recovery after eight weeks. In contexts where primary healthcare is adequate, the systematic use of antibiotics in treatment protocols for uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition could be avoided.

Given that in-hospital child mortality remains high, especially in resource-limited settings, the Clean Kids study aimed to assess the risk of nosocomial infection and multidrug resistance in hospitalised children with severe acute malnutrition. The study showed that the prevalence of community-acquired bacteremia was at least 9.1% on admission, while nosocomial infections were estimated at 1.2%. Infections therefore appear to be a major factor in mortality among hospitalised children suffering from severe malnutrition. In addition, resistance to first-line antibiotics was common.