Bangladesh: One person in five infected with hepatitis C in Rohingya refugee camps, but no access to diagnosis or treatment

“Every day, hundreds of patients line up in a seemingly endless queue outside the MSF specialised clinic in Cox's Bazar in the hope of being cured. They have witnessed the devastation caused by hepatitis C, having lost family members here or when they were living in Myanmar,” explains Dr Wasim Firuz, deputy medical coordinator at MSF.

For the past four years, he and his team have been able to treat only a tiny proportion of the Rohingya refugees affected by this infectious disease, which is often diagnosed in several members of the same family. This is the case of Mujibullah, whose wife and two sisters are infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). His mother, who has now died from it, was worried that the virus would spread to the whole family; and about the cost of treatment.

In response, Epicentre conducted a survey of 680 households in seven camps between May and June 2023 to assess the prevalence of HCV infection, which if left untreated can lead to complications such as cirrhosis or liver cancer. The results show that almost a third of the adults in the camps have been exposed to hepatitis C infection at some point in their lives and that 20 per cent have an active hepatitis C infection. Extrapolating the results of this study to all the camps would suggest that about one in five adults is currently living with a hepatitis C infection – totalling an estimated 86,000 individuals – and requiring treatment to be cured. Since October 2020, MSF has seen more than 8,000 patients; that’s between 150 and 200 new patients every month, but even this number of consultations is not sufficient to meet the needs

Effective treatment, limited access

Access to diagnosis and treatment remains inadequate in many low- and middle-income countries, as is the case in Bangladesh. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that hepatitis C had led to the deaths of 242,000 people worldwide, mainly from complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer. Since 2014, direct-acting antivirals have made it possible to treat hepatitis C effectively. MSF teams used these treatments to treat around 19,000 people in Cambodia between 2016 and 2021. After the emergence of the camps in Cox's Bazar, MSF decided to launch a simplified model for the treatment of hepatitis C in the Rohingya community in 2020, based on the one in Cambodia.

Access to diagnosis and treatment remains inadequate in many low- and middle-income countries, as is the case in Bangladesh. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that hepatitis C had led to the deaths of 242,000 people worldwide, mainly from complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer. Since 2014, direct-acting antivirals have made it possible to treat hepatitis C effectively. MSF teams used these treatments to treat around 19,000 people in Cambodia between 2016 and 2021. After the emergence of the camps in Cox's Bazar, MSF decided to launch a simplified model for the treatment of hepatitis C in the Rohingya community in 2020, based on the one in Cambodia.

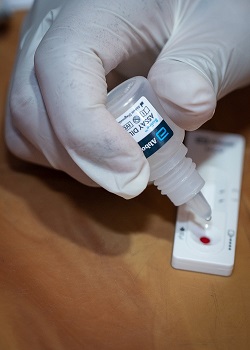

This approach is based on starting treatment for 12 weeks, or even 24 weeks for the most severe forms, without any prior biological assessment of the liver," explains Dr Farah Hossain, Deputy Head of Medical Programmes at MSF. It is accompanied by rapid diagnostic tests to assess the presence of any other associated pathologies (HIV, HBV, diabetes) and a reduced number of follow-up visits. The quality of care has been maintained, as demonstrated by the good therapeutic response, with over 94% cure rate, in more than 4,000 patients".

Although Bangladesh has a plan to combat viral hepatitis, the cost of diagnosis and treatment remains high. Each diagnostic test, for example, costs 20 US dollars and each person tested must be tested twice, with a total cost of 40 US dollars per person, which further increases the medical costs borne by patients.

In the Cox's Bazar camps, MSF clinics are the only places offering free treatment, so this is where hundreds of Rohingya go. They have been living in precarious conditions since 2017; and remain living in camps they cannot leave and where they are reliant on humanitarian aid as they are not allowed to work.

“Unfortunately, we cannot treat everyone because of limited resources. We treat people aged between 40 and 70,” explains Dr Wasim. “Younger people have a chance of self-remission and it usually take years for them to develop complications, while older people are more vulnerable.”

Massive need for treatment in the camps

Hepatitis C is blood-borne and is usually transmitted through unsterilised needles and unsafe medical practices. According to the study carried out by Epicentre, exposure to these practices could be the main risk factor in the specific and confined context of the camps.

Around 70 per cent of the people who took part in the MSF study reported having received therapeutic injections, either in the camps in Bangladesh or in Myanmar, often in medical establishments, from traditional healers or during childbirth carried out in the traditional way. Harsh living conditions in cramped and overcrowded camps, lack of access to healthcare, lack of legal status and reduced healthcare provision have made Rohingya refugees more vulnerable to infections, including hepatitis C.

Breaking the chain of transmission

Enormous progress has been made in the treatment of hepatitis C in recent years, with success rates of up to 95 per cent, thanks to the new direct-acting antivirals. This rate is also being observed by

MSF teams in the Cox's Bazar camps. A massive HCV testing and treatment campaign needs to be implemented in all Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, which requires a rapid increase in access to testing and treatment.

“At the same time, we need to break the chain of transmission through a large-scale prevention and health promotion campaign,” says Dr Farah Hossain. “A multi-partner initiative involving humanitarian and health players is needed to coordinate these efforts.”

Most people with HCV have no symptoms until the disease becomes serious, threatening their lives after many years of progression, leading to jaundice or liver cancer.

“If HCV is detected and treated in time, it can be eliminated, thereby preserving the health of the liver,” continues Dr Farah Hossain. “In the long term, the integration of hepatitis C treatment in all health centres is necessary to prevent new cases and break the transmission chain.”

MSF is currently working with the Bangladesh Ministry of Health to draw up a national plan for the treatment of hepatitis C, based on the simplified treatment model implemented in the camps.

The simplified model of care, ready to be shared with all the medical actors in the camps, should facilitate the use of HCV tests and treatment. Health education campaigns are needed to address the lack of information on HCV prevention in the camps. Community activities to combat stigma and discrimination must also be implemented.